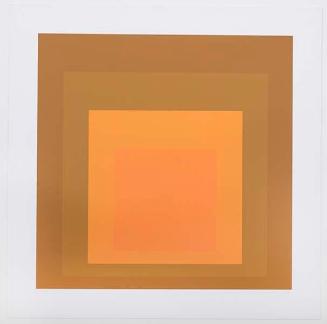

Skip to main contentBiographyTextile designer, draughtsman and printmaker, wife of (1) Josef Albers. She studied art under Martin Brandenburg (b 1870) in Berlin from 1916 to 1919, at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg (1919–20) and at the Bauhaus in Weimar (1922–5) and Dessau (1925–9; see fig.). In 1925 she married (1) Josef Albers, with whom she settled in the USA in 1933 after the closure of the Bauhaus, and from 1933 to 1949 she taught at BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE in North Carolina; she became a US citizen in 1937. Her Bauhaus training led her as early as the 1920s to produce rectilinear abstract designs based on colour relationships, such as Design for Rug for Child’s Room (gouache on paper, 1928; New York, MOMA), but it was during her period at Black Mountain College that she began producing her most original work, including fabrics made of unusual materials such as a mixture of jute and cellophane (1945–50; New York, MOMA) or of mixed warp and heavy linen weft with jute, cotton and aluminium (1949; New York, MOMA). She began producing prints in 1963, using lithography, screenprinting, etching and aquatint and inkless intaglio (see exh. cat., pp. 106–30). (SOURCE: Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T001503pg2?q=anni+albers&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit, Accessed October 3rd, 2016)

The daughter of a furniture manufacturer, Anni Albers (née Fleischmann) was born in Berlin. After studying art with a private tutor, and then with impressionist painter Martin Brandenburg, she continued her training at the School of Applied Art in Hamburg and the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau. At the Weimar Bauhaus she met abstract artist Josef Albers, whom she married in 1925. She was a part-time instructor and acting director of the Bauhaus weaving workshop from 1930 to 1933. The couple left Nazi Germany and accepted teaching positions at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, where Anni Albers was an assistant professor of art from 1933 to 1949.

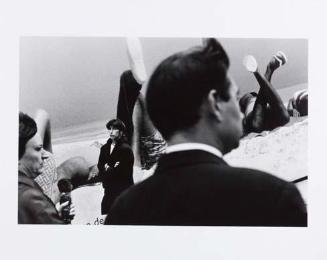

Albers was the first weaver to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1949, and the second recipient of the American Craft Council's Fold Medal for "uncompromising excellence" in 1980.

Kenneth R. Trapp and Howard Risatti Skilled Work: American Craft in the Renwick Gallery (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998) (SOURCE, Smithsonian American Art Museum, http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artist/?id=45, Accessed, October

20, 2016).

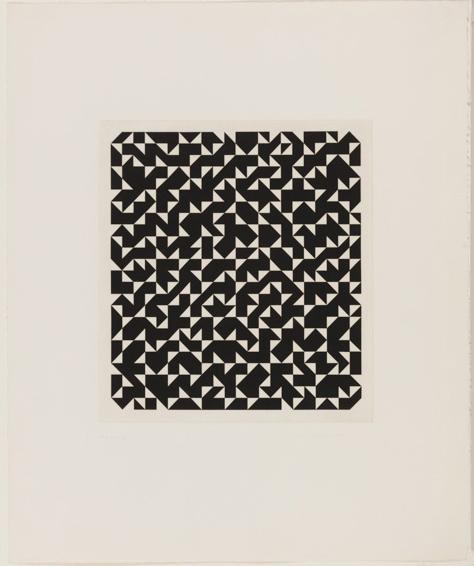

In the same year Albers created Triangulated Intaglios I, her husband, Josef Albers, passed away. (SOURCE, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, http://www.albersfoundation.org/artists/chronology/overview/ Accessed: October 20, 2016).

In addition to creating striking designs for utilitarian woven objects, she helped to reestablish work in textiles as an art form.

Before joining the Bauhaus school at Weimar, Germany, in 1922, she studied painting with Martin Brandenburg in Berlin. She completed the preliminary course at the Bauhaus, and, although she initially had little interest in weaving, she was placed into the Weaving Workshop (then considered a feminine art). Despite her initial skepticism, she came to enjoy the challenges of that medium and experimented with weaving unusual substances. In 1925 she married, and that same year she and Josef moved with the Bauhaus (where he was appointed a Bauhaus master) to Dessau. She was awarded a diploma in 1929, after she designed an innovative auditorium wall covering (using cotton, chenille, and cellophane) that both reflected light and absorbed sound. Architect Philip Johnson, who as a young man was instrumental in helping the couple escape Nazi Germany, later called that wall covering her “passport to America.”

When the Nazis forced the Bauhaus school to close in 1933, Albers (who was Jewish) and her husband went to the United States, where Josef had been invited to teach at Black Mountain College, a newly opened experimental liberal arts school near Black Mountain, North Carolina. Both became U.S. citizens in 1939. While at Black Mountain (1933–49), Anni Albers developed a weaving curriculum that focused on industrial design, a course of study she later described in her book On Weaving (1965). During that time, she continued to try out nontraditional materials—such as harness maker’s thread, hemp, plastic, and Lurex (synthetic metal thread). She also worked at the intersection between handwoven and industrial textiles and became a student and collector of ancient Peruvian textiles. (SOURCE, Britannica Academic, http://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/604743, Accessed: October 20, 2016)

Anni Albers

American, born Germany, 1899 - 1994

The daughter of a furniture manufacturer, Anni Albers (née Fleischmann) was born in Berlin. After studying art with a private tutor, and then with impressionist painter Martin Brandenburg, she continued her training at the School of Applied Art in Hamburg and the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau. At the Weimar Bauhaus she met abstract artist Josef Albers, whom she married in 1925. She was a part-time instructor and acting director of the Bauhaus weaving workshop from 1930 to 1933. The couple left Nazi Germany and accepted teaching positions at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, where Anni Albers was an assistant professor of art from 1933 to 1949.

Albers was the first weaver to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1949, and the second recipient of the American Craft Council's Fold Medal for "uncompromising excellence" in 1980.

Kenneth R. Trapp and Howard Risatti Skilled Work: American Craft in the Renwick Gallery (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998) (SOURCE, Smithsonian American Art Museum, http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artist/?id=45, Accessed, October

20, 2016).

In the same year Albers created Triangulated Intaglios I, her husband, Josef Albers, passed away. (SOURCE, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, http://www.albersfoundation.org/artists/chronology/overview/ Accessed: October 20, 2016).

In addition to creating striking designs for utilitarian woven objects, she helped to reestablish work in textiles as an art form.

Before joining the Bauhaus school at Weimar, Germany, in 1922, she studied painting with Martin Brandenburg in Berlin. She completed the preliminary course at the Bauhaus, and, although she initially had little interest in weaving, she was placed into the Weaving Workshop (then considered a feminine art). Despite her initial skepticism, she came to enjoy the challenges of that medium and experimented with weaving unusual substances. In 1925 she married, and that same year she and Josef moved with the Bauhaus (where he was appointed a Bauhaus master) to Dessau. She was awarded a diploma in 1929, after she designed an innovative auditorium wall covering (using cotton, chenille, and cellophane) that both reflected light and absorbed sound. Architect Philip Johnson, who as a young man was instrumental in helping the couple escape Nazi Germany, later called that wall covering her “passport to America.”

When the Nazis forced the Bauhaus school to close in 1933, Albers (who was Jewish) and her husband went to the United States, where Josef had been invited to teach at Black Mountain College, a newly opened experimental liberal arts school near Black Mountain, North Carolina. Both became U.S. citizens in 1939. While at Black Mountain (1933–49), Anni Albers developed a weaving curriculum that focused on industrial design, a course of study she later described in her book On Weaving (1965). During that time, she continued to try out nontraditional materials—such as harness maker’s thread, hemp, plastic, and Lurex (synthetic metal thread). She also worked at the intersection between handwoven and industrial textiles and became a student and collector of ancient Peruvian textiles. (SOURCE, Britannica Academic, http://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/604743, Accessed: October 20, 2016)

Person TypeIndividual

Diné (Navajo), 1948 – 2021