Skip to main contentBiographyBorn: Mexico City (Distrito Federal, Mexico)

Died: Mexico City (Distrito Federal, Mexico)

Mexican photographer. Álvarez Bravo’s interest in photography began in his adolescence while living in Mexico City in the 1910s, the years of the Mexican Revolution. He left school at the age of 13 to help support his family but pursued his creative interests by studying foreign photography magazines and receiving instruction from the German photographer based in Mexico, Hugo Brehme. Álvarez Bravo’s earliest images, made with a large-format Graflex camera, reflected the romantic pictorialist mode identified with Brehme’s generation. By 1925, however, he turned to a modernist aesthetic inspired by the photographs Edward Weston made in Mexico in the mid-1920s as well as those of Tina Modotti, who accompanied Weston and remained in the country until 1930. During this era Álvarez Bravo came to know Modotti as well as the artists who led Mexico’s cultural renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, including Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and Rufino Tamayo. Also central to this circle was LOLA ÁLVAREZ BRAVO, whom he married in 1924 and who eventually became a significant photographer in her own right (they separated in 1934 and divorced several years later).

Álvarez Bravo produced essentially all his work in Mexico. His first mature photographs in the late 1920s include spare, composed scenes of common forms like a stack of books, tools, or rolls of accounting paper. His classic images of the 1930s meld a keen sense of observation with a seemingly uncanny ability to infuse the everyday with metaphorical value, and often, with a sense of poetic possibility. Optic Parable (1931), a reversed image of an optician’s storefront filled with pictures of eyes, expresses vision as a physical, spiritual, and creative entity. It is one of many photographs by Álvarez Bravo highlighting the cultural incongruities visible amidst the urban landscape of Mexico City, then a rapidly modernizing city, but one with a large peasant population and ancient indigenous roots. Álvarez Bravo also depicted anonymous everyday people, who acted as much as symbols for the Mexican cultural heritage he cherished as nuanced studies in human behaviour.

In 1935 Álvarez Bravo exhibited with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York; he subsequently travelled to Chicago where he taught and exhibited at Hull House. When André Breton visited Mexico, he featured Álvarez Bravo in the 1940 Exposition of Surrealism, held in Mexico City. Although Álvarez Bravo did not consider himself a Surrealist, he created one of his most iconic images, Good Reputation Sleeping (1939), as a result of a ‘surrealist impulse’. This enigmatic composition of a reclining woman whose feet and upper thighs are wrapped with lengths of bandage evinces Álvarez Bravo as a photographer of enormous psychological depth. The female nude was one of his abiding themes, particularly later in his life.

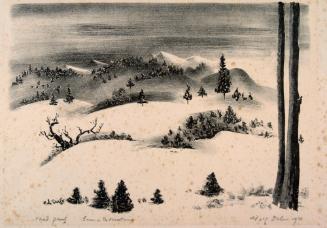

Álvarez Bravo worked as a still photographer in Mexico’s film industry in the 1940s and 1950s, decades known as the nation’s Golden Age of cinema. He continued to photograph in this period, often picturing arid landscapes, workers, and simply people walking along city streets framed by tall walls. His long career also encompassed teaching, filmmaking, publishing, and curating. (SOURCE: [Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T002194?q=manuel+alvarez+Bravo&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit, January 20, 2017])

Manuel Álvarez Bravo

Mexican, 1902 - 2002

Died: Mexico City (Distrito Federal, Mexico)

Mexican photographer. Álvarez Bravo’s interest in photography began in his adolescence while living in Mexico City in the 1910s, the years of the Mexican Revolution. He left school at the age of 13 to help support his family but pursued his creative interests by studying foreign photography magazines and receiving instruction from the German photographer based in Mexico, Hugo Brehme. Álvarez Bravo’s earliest images, made with a large-format Graflex camera, reflected the romantic pictorialist mode identified with Brehme’s generation. By 1925, however, he turned to a modernist aesthetic inspired by the photographs Edward Weston made in Mexico in the mid-1920s as well as those of Tina Modotti, who accompanied Weston and remained in the country until 1930. During this era Álvarez Bravo came to know Modotti as well as the artists who led Mexico’s cultural renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, including Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and Rufino Tamayo. Also central to this circle was LOLA ÁLVAREZ BRAVO, whom he married in 1924 and who eventually became a significant photographer in her own right (they separated in 1934 and divorced several years later).

Álvarez Bravo produced essentially all his work in Mexico. His first mature photographs in the late 1920s include spare, composed scenes of common forms like a stack of books, tools, or rolls of accounting paper. His classic images of the 1930s meld a keen sense of observation with a seemingly uncanny ability to infuse the everyday with metaphorical value, and often, with a sense of poetic possibility. Optic Parable (1931), a reversed image of an optician’s storefront filled with pictures of eyes, expresses vision as a physical, spiritual, and creative entity. It is one of many photographs by Álvarez Bravo highlighting the cultural incongruities visible amidst the urban landscape of Mexico City, then a rapidly modernizing city, but one with a large peasant population and ancient indigenous roots. Álvarez Bravo also depicted anonymous everyday people, who acted as much as symbols for the Mexican cultural heritage he cherished as nuanced studies in human behaviour.

In 1935 Álvarez Bravo exhibited with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York; he subsequently travelled to Chicago where he taught and exhibited at Hull House. When André Breton visited Mexico, he featured Álvarez Bravo in the 1940 Exposition of Surrealism, held in Mexico City. Although Álvarez Bravo did not consider himself a Surrealist, he created one of his most iconic images, Good Reputation Sleeping (1939), as a result of a ‘surrealist impulse’. This enigmatic composition of a reclining woman whose feet and upper thighs are wrapped with lengths of bandage evinces Álvarez Bravo as a photographer of enormous psychological depth. The female nude was one of his abiding themes, particularly later in his life.

Álvarez Bravo worked as a still photographer in Mexico’s film industry in the 1940s and 1950s, decades known as the nation’s Golden Age of cinema. He continued to photograph in this period, often picturing arid landscapes, workers, and simply people walking along city streets framed by tall walls. His long career also encompassed teaching, filmmaking, publishing, and curating. (SOURCE: [Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T002194?q=manuel+alvarez+Bravo&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit, January 20, 2017])

Person TypeIndividual

Diné (Navajo), 1948 – 2021

Native American [Cochiti Pueblo], 1932 – 1997