Skip to main contentBiographyA political leftist and social activist, Gertrude Greene avoided overt commentary in her art. Unlike Louis Schanker, Hananiah Harari, and others for whom art expressed societal concerns, natural forms, and structures, Greene looked to the purity of Mondrian and Russian Constructivists Antoine Pevsner, Naum Gabo, and Vladimir Tatlin for her artistic foundations.

Greene began studying sculpture at the Leonardo da Vinci School in NewYork in 1924. The curriculum at the Leonardo school paralleled the foundation classes at the National Academy of Design and other conservative art schools—students studied life drawing only after demonstrating proficiency in drawing from plaster casts. Greene's art interests carried over into the kindergarten she ran at the time; on rainy days, she took her young charges to the Brooklyn Museum where the students attempted to draw the sculpture and paintings.(1)

In 1926, Greene, née Glass, married Balcomb Greene. The young couple soon left for Vienna where Balcomb pursued graduate work in psychology. After a year abroad, they returned to New York via Paris, and in 1928, Balcomb accepted a teaching position at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. During their three years in New Hampshire, the Greenes visited New York often. They frequented Gallatin's Gallery of Living Art and the newly opened Museum of Modern Art. This whetted Greene's appetite to see more vanguard art, and by late 1931, the couple had saved enough money to return to Paris.

Paris in the late 1920s and early 1930s offered remarkable opportunities for young artists seeking the avant-garde. Not only was the city the center for Cubism and Surrealism, but, with the formation of Abstraction-Création, Art Nonfiguratif, Constructivism was very much in evidence. The goal of this group, wrote sculptor Naum Gabo in the first issue of the eponymous publication, was the "cultivation of pure plastic art, to the exclusion of all explanatory, anecdotal, literary and naturalistic elements."

Greene, especially, became fascinated with the Constructivists, ideas about unifying art and politics—thoughts that grew out of their belief that when "purified," art would show the way for reordering society along higher planes. Even more than the theory, however, Greene was impressed with Pevsner's and Gabo's art, and began doing Constructivist drawings. After the Greenes returned to New York, Gertrude became active in leftist artists' organizations. She helped establish the Unemployed Artists' Group that was formed to lobby for federal support for unemployed painters, sculptors, and printmakers.

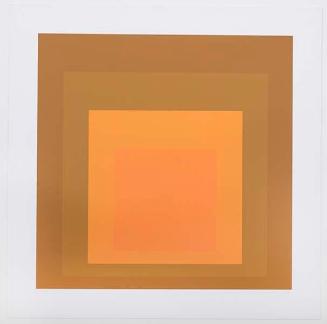

Throughout the 1930s, Greene's art progressed almost systematically toward geometrical purity. By 1935, the year the Museum of Modern Art presented excellent examples of work by Malevich, El Lissitzky, Rodchenko, Tatlin, and Pevsner in an exhibition entitled Cubism and Abstract Art, she herself had begun making constructions. Initially indicative of herappreciation for Jean Arp's work, Greene'sconstructions over the next two years moved between biomorphic and geometric abstraction. Increasingly, however, she began merging the two types of forms—one associated with Surrealism, the other with Constructivism—and after about 1940, a simple, geometric approach akin to Neo-plasticism and Constructivism predominated. As studies for these works, she began making paper collages that explored the merging of biomorphic and geometric form and experimented with layering as a spatial device.(2)

In her last constructions, such as Construction 1946, Greene began adding gestural areas of color. Although among her strongest and most original accomplishments, she put aside her relief constructions in favor of painting. Initially geometric, her paintings by the early 1950s became increasingly expressionistic. Her solo exhibitions, in 1951 and 1955, the first of her career, included only the late, gestural canvases.

In 1937, when the American Abstract Artists was formed, Greene was its first paid employee. She tended the desk at the Squibb Gallery exhibition in 1937, passing out questionnaires and answering the queries and jibes about the art that was featured in the first annual show. Her own work was also shown that year in the opening exhibition of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting.

Although she resigned her membership in the American Abstract Artists in 1942, only five years after the first exhibition, Greene did so in the belief that the group's mission had been largely accomplished. She had figured prominently in the group's programs and in promoting the purist point of view in arguments over the role of nature versus geometric purity in abstract art.

1. For additional biographical information, see Lynda Hyman, Gertrude Greene: Constructions, Collages, Paintings (NewYork: ACA Galleries, 1981).

2. Jacqueline Moss, "Gertrude Greene: Constructions of the 1930s and 1940s," Arts Magazine 55, no. 8 (April 1981): 123, reports that Greene destroyed many of her collages.

SOURCE: Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)

Image Not Available

for Gertrude Glass Greene

Gertrude Glass Greene

American, 1904 - 1956

Greene began studying sculpture at the Leonardo da Vinci School in NewYork in 1924. The curriculum at the Leonardo school paralleled the foundation classes at the National Academy of Design and other conservative art schools—students studied life drawing only after demonstrating proficiency in drawing from plaster casts. Greene's art interests carried over into the kindergarten she ran at the time; on rainy days, she took her young charges to the Brooklyn Museum where the students attempted to draw the sculpture and paintings.(1)

In 1926, Greene, née Glass, married Balcomb Greene. The young couple soon left for Vienna where Balcomb pursued graduate work in psychology. After a year abroad, they returned to New York via Paris, and in 1928, Balcomb accepted a teaching position at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. During their three years in New Hampshire, the Greenes visited New York often. They frequented Gallatin's Gallery of Living Art and the newly opened Museum of Modern Art. This whetted Greene's appetite to see more vanguard art, and by late 1931, the couple had saved enough money to return to Paris.

Paris in the late 1920s and early 1930s offered remarkable opportunities for young artists seeking the avant-garde. Not only was the city the center for Cubism and Surrealism, but, with the formation of Abstraction-Création, Art Nonfiguratif, Constructivism was very much in evidence. The goal of this group, wrote sculptor Naum Gabo in the first issue of the eponymous publication, was the "cultivation of pure plastic art, to the exclusion of all explanatory, anecdotal, literary and naturalistic elements."

Greene, especially, became fascinated with the Constructivists, ideas about unifying art and politics—thoughts that grew out of their belief that when "purified," art would show the way for reordering society along higher planes. Even more than the theory, however, Greene was impressed with Pevsner's and Gabo's art, and began doing Constructivist drawings. After the Greenes returned to New York, Gertrude became active in leftist artists' organizations. She helped establish the Unemployed Artists' Group that was formed to lobby for federal support for unemployed painters, sculptors, and printmakers.

Throughout the 1930s, Greene's art progressed almost systematically toward geometrical purity. By 1935, the year the Museum of Modern Art presented excellent examples of work by Malevich, El Lissitzky, Rodchenko, Tatlin, and Pevsner in an exhibition entitled Cubism and Abstract Art, she herself had begun making constructions. Initially indicative of herappreciation for Jean Arp's work, Greene'sconstructions over the next two years moved between biomorphic and geometric abstraction. Increasingly, however, she began merging the two types of forms—one associated with Surrealism, the other with Constructivism—and after about 1940, a simple, geometric approach akin to Neo-plasticism and Constructivism predominated. As studies for these works, she began making paper collages that explored the merging of biomorphic and geometric form and experimented with layering as a spatial device.(2)

In her last constructions, such as Construction 1946, Greene began adding gestural areas of color. Although among her strongest and most original accomplishments, she put aside her relief constructions in favor of painting. Initially geometric, her paintings by the early 1950s became increasingly expressionistic. Her solo exhibitions, in 1951 and 1955, the first of her career, included only the late, gestural canvases.

In 1937, when the American Abstract Artists was formed, Greene was its first paid employee. She tended the desk at the Squibb Gallery exhibition in 1937, passing out questionnaires and answering the queries and jibes about the art that was featured in the first annual show. Her own work was also shown that year in the opening exhibition of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting.

Although she resigned her membership in the American Abstract Artists in 1942, only five years after the first exhibition, Greene did so in the belief that the group's mission had been largely accomplished. She had figured prominently in the group's programs and in promoting the purist point of view in arguments over the role of nature versus geometric purity in abstract art.

1. For additional biographical information, see Lynda Hyman, Gertrude Greene: Constructions, Collages, Paintings (NewYork: ACA Galleries, 1981).

2. Jacqueline Moss, "Gertrude Greene: Constructions of the 1930s and 1940s," Arts Magazine 55, no. 8 (April 1981): 123, reports that Greene destroyed many of her collages.

SOURCE: Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)

Person TypeIndividual